The Pinch

The Punch

Lately I feel like I can’t open my inbox without being slapped in the soul by another disturbing article about climate change and the destruction of our planet. I’m not suggesting that these pieces aren’t important, or shouldn’t be written—we need awareness and action, and awareness fueled by fear and outrage often does inspire action—but I don’t read them anymore. It’s my daily act of self-kindness to avoid pouring gasoline on the pilot light of my anxiety.

This month’s newsletter is not about climate anxiety, but it’s not entirely unrelated; it’s about animism, Haitian Vodou, and panpsychism, three systems I have encountered over the years that have touched me and shaped my sense of how I want to be in the world. They are glimpses into a different kind of human-nature relationship that I find beautiful and hopeful. They are systems that propose an animate, irreplaceable, and sacred world.

Confession: I have in the past been highly skeptical of the word “sacred” and the people who breathlessly utter it while banging on about crystals, energy, and, yes, Mother Earth. But the world views I’m about to touch on have offered me an understanding of “sacred” that is as earthy as it is transcendent, that is connected to a reverent appreciation for our deeply mysterious yet very tangible world—a world that requires us to integrate knowns and unknowns, the physical with the metaphysical.

Einstein said that you can’t solve a problem with the same mind that created it. We have a big problem caused by some very bad ways of thinking about and treating our environment, and the many other animate and seemingly inanimate beings that comprise our global ecosystem.

But what if we could, as a collective species, begin to change our whole orientation to the world? To have a more mutual and less narcissistic and exploitative relationship with the earth? I’m not sure what this would look like practically. Our current crisis is much more complicated than a-holes littering in forests. And no matter how well-intentioned and tree-hugging one may be, it’s extremely difficult to live without doing harm in some way or another (everything is packaged in motherfluffing plastic!)—even if those ways are small compared to the biggest (corporate) offenders.

But maybe the first step in any endeavor is a change in perception.

The word “animism” has at its root the Latin anima—breath, spirit, life. I like this definition: the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct spiritual essence. I first encountered animistic principles by way of Hayao Miyazaki’s beautiful animated films. I won’t go into Miyazaki’s incredible body of work here—there are plenty of great scholarly articles on his oeuvre and its themes, which include man’s moral ambiguity, the relationship between new and old world ways, and the dangers of unfettered materialism. But as a kid, I was captivated by the enchanted lands and beings depicted in My Neighbor Totoro and Princess Mononoke. The worlds they portrayed were beautiful and alive, inhabited and animated by spirits. The protagonists of these films, whether adults or children, related to the natural spaces they encountered with wonder and respect. They seemed to understand that the world was active, listening, and responsive in its own ways.

This made sense to me—as a kid I remember seeing trees and plants and animals as beings not so different from people, with the potential to feel and think and speak. Maybe lots of kids have this anthropomorphizing tendency, which we “grow out of” later.

In any case, nature in Miyazaki’s films is not a passive, dead arena for human activity; it is just as alive and relational as you or I, although its consciousness looks different from that of human beings. He describes the kodama, the forest-dwelling spirit beings in Princess Mononoke, as expressing “’something unseen’ that exists in the forest,” namely the unseen yet very real forces of life. I was well acquainted with this idea years later, when I began studying Haitian Vodou.

(As a silly aside, Mason Currey’s screenshots of Miyazaki exemplifying the Tortured Artist are delightful).

I learned about Vodou as a student of its dances and rhythms, and avidly studied it all through my twenties. It’s a profoundly misunderstood religion whose depth is way beyond my own humble studies, but as a brief overview: Vodou is a syncretism, the result of West/Central African religions meeting and absorbing the cosmologies of Carib, Arawak, and Guanahatabey people indigenous to the island that is now Haiti/Dominican Republic. It also includes elements of Catholicism and Freemasonry, introduced by those dang French colonialists (and other Europeans).

Vodou has a huge pantheon of spiritual entities called lwa. Many are derived from Yoruba, Fon, Ibo, Congo, and Ewe spirits; some also have Catholic saint counterparts. Unlike the ultimate creator God, who is so almighty and mysterious and strange as to be completely beyond our puny human comprehension, lwa are spiritual intermediaries we can recognize, relate to, and be in direct relationship with. They sort of resemble us: each has a distinct personality, an area of expertise, likes and dislikes. They help us out, guide us, at times hinder and frustrate us.

Most importantly, they are not remote supernatural beings: they are embedded in the world. They preside over and are part of nature. Here is a description of the lwa from an excellent article:

“[Lwa] are also thought to manifest in all realms of nature; in the trees, in the mountains, water, air, and fire… lwa are thought to collaborate in their creation of the structure of the natural world, and of time and space.”

To give just a few examples: there is Damballah, who is depicted as a white serpent, and his wife Ayida Wedo, a rainbow. Agwe rules over the sea, fish, and underwater plants, and is the patron of sailors and fishermen. His wife, Lasirenn, is “Mistress of Mysticism” and keeper of the sea’s secrets. Gran Bwa lives among wild vegetation and is the protector of woods, herbs, and wildlife. Loko is also linked to plants and is a patron of healers. And there are hundreds more.

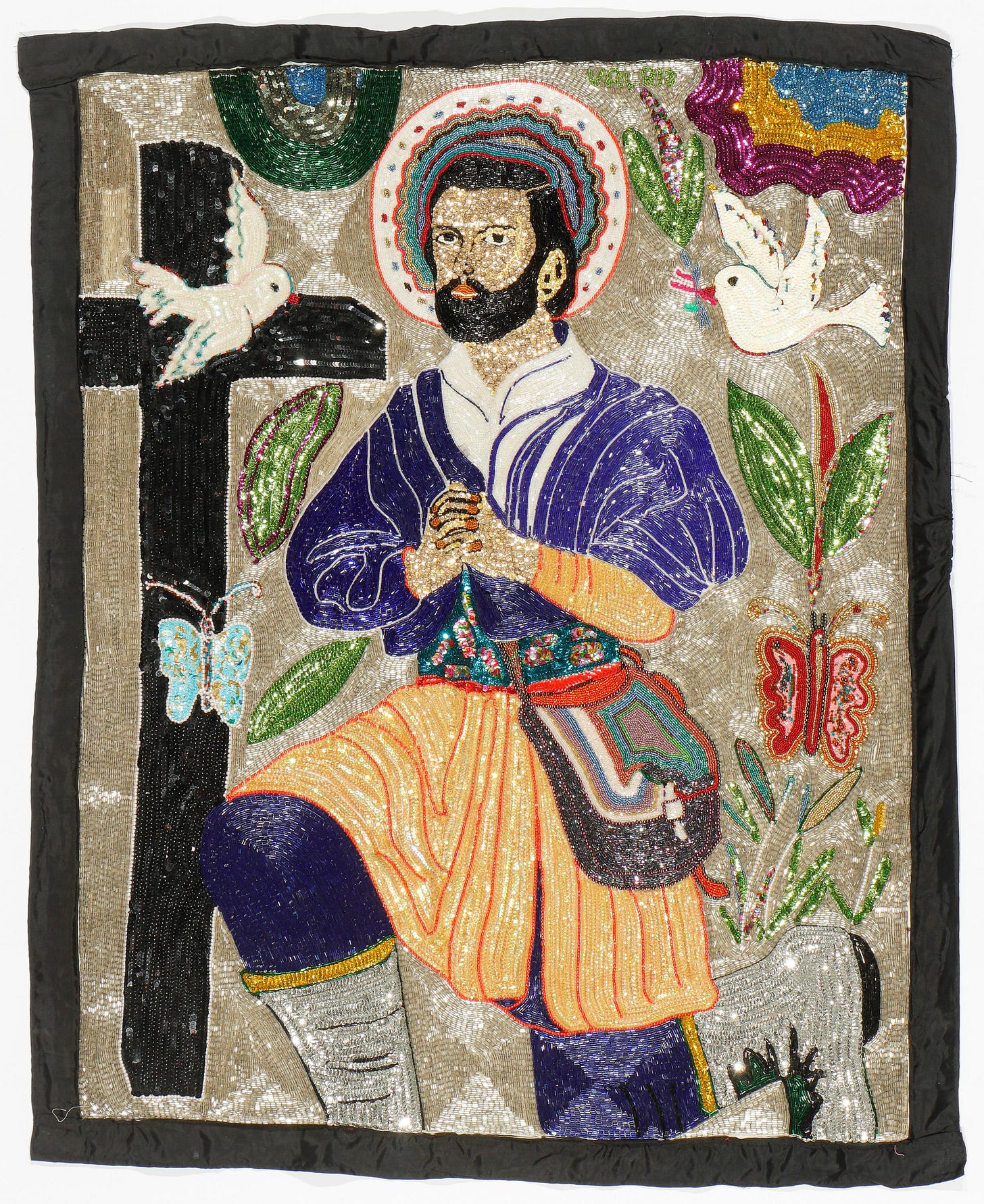

One lwa who is especially close to my heart is Zaka, who represents a particular relationship between humans and nature: agriculture. Zaka is seen as a peasant farmer, and is the patron saint of the harvest and hardworking country-folk. He’s associated with St. Isidore, also a land laborer, although it strikes me that Zaka is less solemn and saintly and more salt-of-the-earth. He’s often called “Kouzen” (cousin), and is essentially a bumpkin. He’s gentle, suspicious of outsiders, goes barefoot and smokes a pipe. He’s a great dancer and a gossip. He’s also a master of treating illness through herbs.

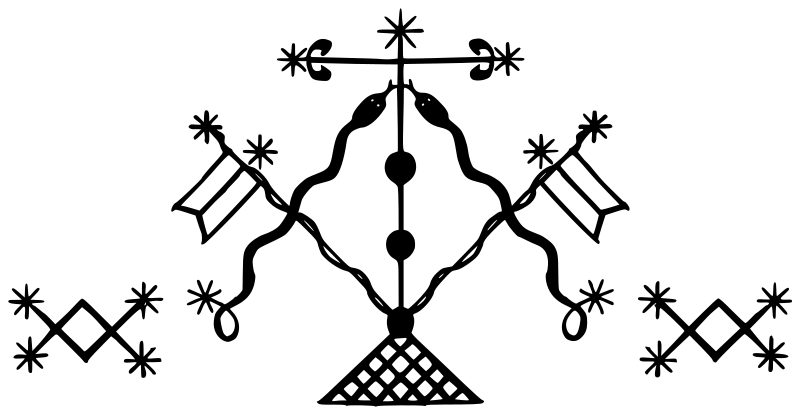

Each lwa is honored/served in its own way, with its own particular vèvè (visual symbol/cosmogram), rhythms, dances, food, and offerings. Here is a short clip of a celebration for Agwe at Jacob Riis Beach in August 2017, proceeding to the ocean with a cake:

Although the details are different, animistic views seem omnipresent among people who deal closely with or are more exposed to life outside of man’s making or control—the life of plants and animals, elements and seasons. When people are in close contact with nature, it’s difficult not to acknowledge the awesome, transcendent something that is at the very core of existence—the existence of all things, rocks and trees and plants and animals, as well as people. I’m no scholar of anthropology or religion, but my superficial observation is that cultures with animistic views seem to see the fundamental connectedness between all things. They understand the need to honor and relate properly to the ecosystems and environments of which we are a part, in order to keep the world (and one’s self) in balance. They acknowledge that we can’t remove ourselves from the world we inhabit any more than we can remove ourselves from our own bodies.

But what about those of us who are living rather removed lives, in a hopelessly plasticized, technology-mediated, post-modern reality? Have our pre-modern gods permanently evaporated in the wake of the Newtonian worldview? Is it possible for us to connect with any of that old-world respect for nature, ecosystems, earth?

In the last few years, I’ve become familiar with the incredible work of Iain McGilchrist. Iain started out as a literary scholar before pivoting to psychiatry and neuroscience. He’s also the best kind of philosopher: one who makes the abstract applicable and connects big ideas with our here-and-now reality. He has devoted decades to research and writing and produced thousands of pages on, among other things, the different ways our left and right brain hemispheres perceive and attend to the world, how this shapes our experience of the world and thus how we operate within it, and what this implies on a larger scale.

Iain is not shy to suggest that our planet is in crisis due to the pathology of humans, namely our pathological way of relating to and operating in the world. As a collective whole, he asserts, we have moved into a way of being and seeing that is dissatisfied, narrow, greedy, and atomistic. More and more, we are prone to view one another and the world as mere things to be exploited and used. Looking around, there is plenty of empirical evidence to suggest he is correct.

You might also call Iain a panpsychist, or at least a proponent of panpsychism. Panpsychism is the view that “the mind or a mindlike aspect is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of reality.” Or as he puts it, that consciousness is not something that’s produced by the material stuff of our brains, but that is received by it. In other words: consciousness is the stuff of material reality—matter is consciousness in another form, just as ice is water in another form:

Iain firmly dismisses the reductionist assumption that the stuff of the world (trees and rocks and rivers, for instance) is merely lifeless matter to be exploited and degraded without consequence. Here he speaks about the mutual encounter between ourselves and the world in Beshara Magazine:

“I’ve always believed, since I was a teenager, that the world is not inert – that we are not just passive photographic plates that register impressions of light, or a recorder that records sounds. It is rather a matter of an encounter – a meeting – in which we go to meet the world and the world comes to meet us in its own terms.”

Iain’s thoughts and theories about the state of the world are sobering, but he gives me hope. The sanctity of our world is a critical point in his work that is not at all in conflict with the work’s scientific rigor. One’s credulity might be stretched too far by the idea of literal tree spirits, but I think Iain would appreciate the symbolic value of believing in and honoring the sacred (if metaphorical) forces of nature. In whatever way we can feel connected with the incredible mystery of the life around us, we are closer to a mutual and deeply personal relationship with this strange planetary jewel.

I’ll end with some wonderful words from Iain’s interview on Rebel Wisdom:

“That’s what I wish for people, that they will make contact again with the vision of a world that is not a heap of pointless fragments; that is not chaotic, ugly, and without meaning; which is not just one in which we are the playthings of chance and embroiled in a war of all against all…but one that is beautiful, intrinsically complex, rich, conscious, and responsive, and is a gift in which we should stand in awe.” (emphasis mine)

Parting updates

In July I had the total pleasure of making some new friends and collaborators while spending two days shooting a music video in Seattle. The forthcoming video is for “Lost Days in Lost Places,” a track I truly adore by songwriter Brandon Krebs and singer/lyricist Whitney Lyman. The editing process is currently under way; hopefully the video will be out this fall. For now, here are a few stills :)